The Academic Browser

Your Librarian in the Cloud

Your Librarian in the Cloud

Picture yourself diving into research on a new topic. You’ve got twenty browser tabs open—Google Scholar here, Semantic Scholar there, a handful of PDFs, and somewhere in that digital maze is the perfect paper you found an hour ago but can’t seem to find again.

In the age of digital research, we’ve traded the quiet halls of physical libraries for a labyrinth of online databases, search engines, and reference managers. While the wealth of available information is unprecedented, the challenge of organizing these digital tools can be as daunting as finding a single book in a library with no catalog system.

What if you could transform your browser into a personal research assistant? Imagine having every research tool at your fingertips, organized just like a well-structured library—dictionaries and encyclopedias in one section, journal databases in another, and powerful analysis tools ready when you need them.

In an earlier post, A Research Rubric, we explored the basics of online journal article searches. Now, we’re taking it further by turning your everyday browser into a sophisticated research companion. No fancy software required—just a alternate method to organize the tools already at your disposal.

Let’s transform that mess of browser tabs into a well-organized digital library that will save you hours of wasted time.

The search process

The first step is to select and install a reference manager (Zotero, Mendeley, Qiqqa, Docear).

The search begins with understanding the terms used by researchers in the field, followed by a high-level look at review articles. Next, do a more focused search for articles related to the topic you’re interested in, and find other articles cited by, or referencing these papers.

Download or bookmark interesting articles, read, summarize, and make sure you understand the relevant papers.

An outline of the process is:

- Search for terms related to the topic using a dictionary or thesaurus.

- Read online encyclopedias to understand the basic ideas. Linked references can be a good source for more information.

- Do a broad search for relevant terms. A commonly applied word or phrase may not be generally used by researchers.

- Look for papers describing the current state of the art in the field. These meta or review articles reference many of the best papers written about a particular topic.

- Use the references in the review articles to find other papers.

- From the targeted papers, follow citations forward and backward to expand your understanding.

- Read, understand, and summarize the best of the papers you’ve found. Ideally, you should read a paper once, and refer to your notes about it later if you want to remember the main topics.

- If you want to publish, you’ll need to reference the articles you’ve read, and a good reference manager is critical to this step. Publishing could be notes to yourself, writing your blog, or submitting to a peer-reviewed journal.

Organizing the tools

I wanted a way to organize the various online tools useful for researchers. My first thought was to do what I’m about to show you, but then I started thinking about making some fancy GUI, maybe in Qt, and making a dedicated browser for the purpose.

The advantage of a dedicated browser is that I wouldn’t get distracted by checking the latest news on CNN and then feeling the need to find a video of monkeys jumping into a pool to make up for the bad karma.

Jan and I talked about this concept, possibly with buttons to automatically open a new tab in the browser linked to the appropriate tool. Jan was rightfully dubious about all of this, pointing out that everyone dives right into building the fanciest widget without fully considering the purpose.

So, back to my first thought, why not just organize links to the online tools in bookmarks? Browsers are already nice GUIs, everyone understands bookmarks, and they’re very flexible. You can add or delete bookmarks, or drag them around inside the bookmark folder to put them in any order you like.

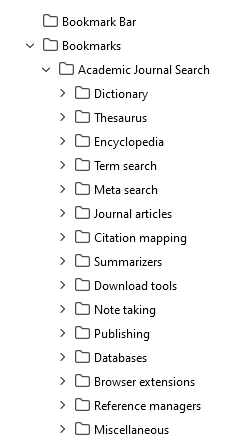

I started by making a dedicated folder called Academic Journal Search. Inside that folder, I created new folders for each step of the search process, plus a few extra folders for links to databases, browser extensions, reference managers, and miscellaneous others.

Browser bookmark organization.

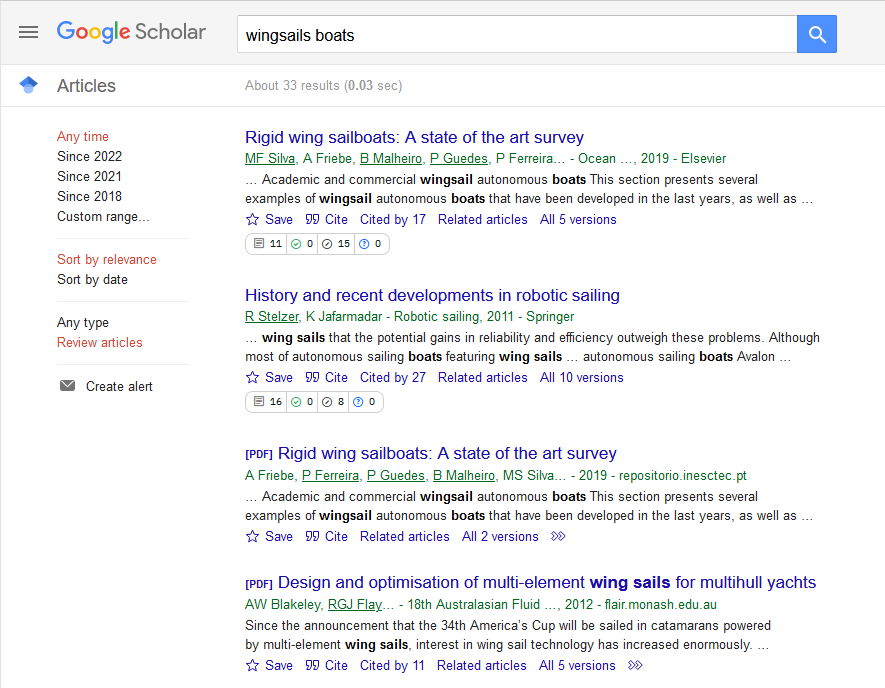

Another advantage to this method of organizing bookmarks is that you can put the same bookmark into more than one folder. For instance, Google Scholar appears in “Meta search” and “Journal articles”. Aaron Tay wrote about a new feature in Google Scholar that searches for review articles. Type in your search term and hit Enter to request review articles.

Google Scholar search.

Other literature databases have similar tools to do meta searches, or you can add “review”, “meta-analysis”, or “systematic reviews” to the search term. You might decide to combine the “Meta search” and “Journal articles” folders into a single folder and use one search engine for each type of search.

A look inside

Dictionaries and Thesauri

To learn about a new topic, you need to understand the definitions and have synonyms handy. The top links in these folders are to Merriam-Webster, but you might have other favorites.

Encyclopedias

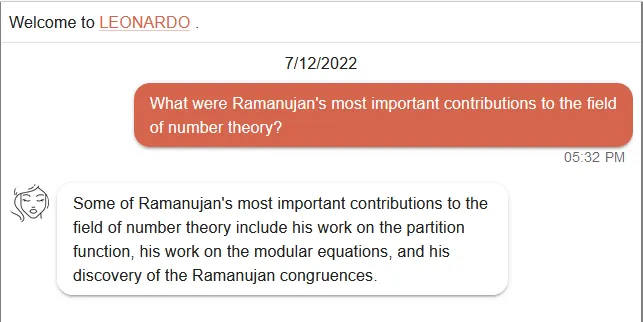

The first link is to Wikipedia, but Scholarpedia might be better if your topic is covered. Scholarpedia is written by subject experts and the articles are peer-reviewed. The scope is mostly physics and math, but if that’s your interest, this is a good resource. Another interesting resource is Leonardo, an AI system designed to answer queries. Be aware that it’s still in beta, and may not give completely accurate answers.

Leonardo AI assisted search.

Term search

Search for basic terms in Google, Bing, or one of several other search engines.

Meta search

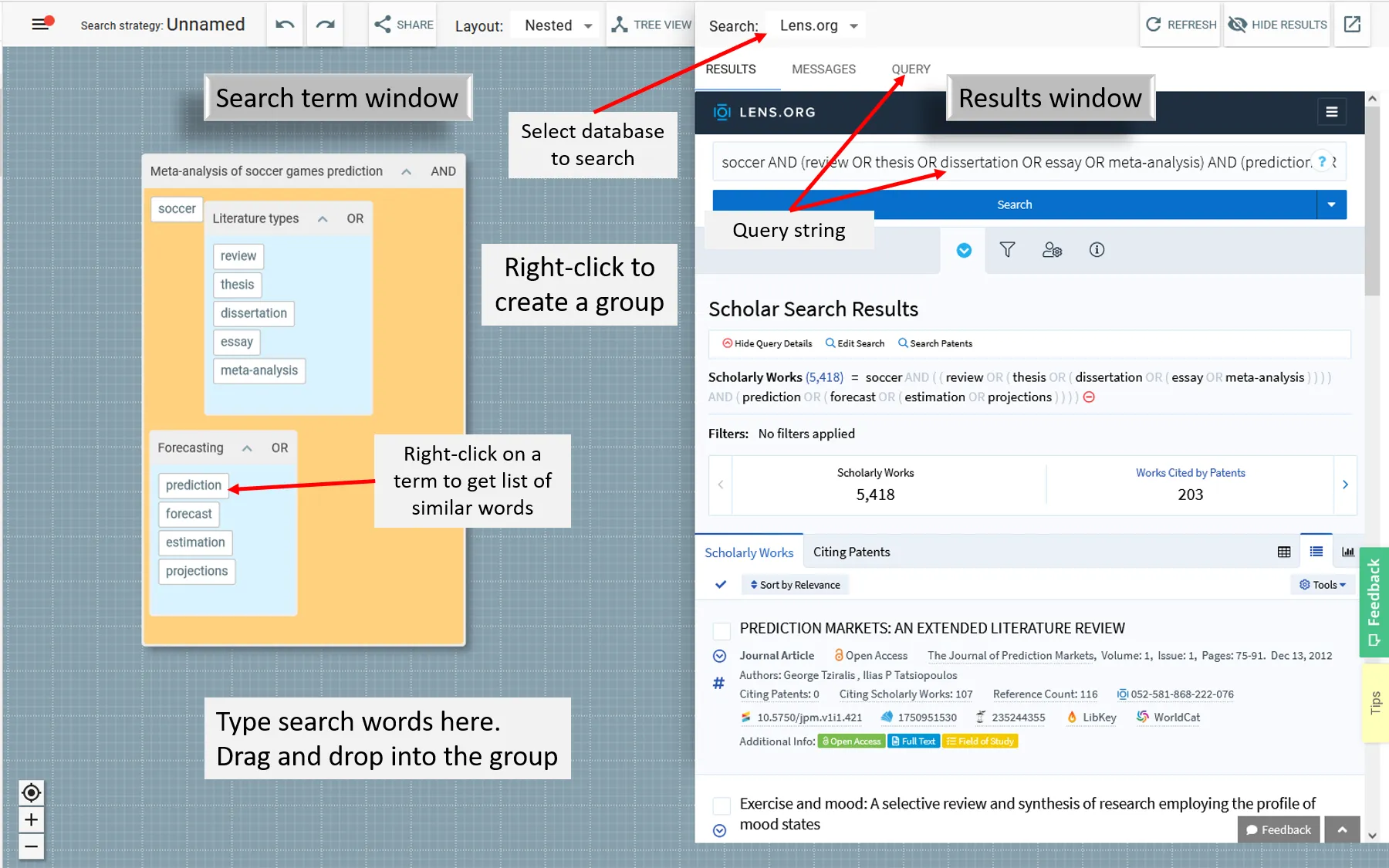

These tools provide much greater capabilities than a simple Google search. 2DSearch lets you graphically build a query, and suggests synonyms. Use Boolean operators to combine terms, and select the literature database to search for papers about your topic.

2DSearch graphical query builder.

Inciteful discovers papers linked to a given article through references, and the Literature Connector tool finds the citation links from one paper to another.

The litserachr package for R lets you apply advanced search techniques programmatically. It’s also available online with slightly reduced functionality.

Journal articles

In the Journal articles folder, you’ll find search engines specifically designed to look for papers of interest. Google Scholar is a good start, but Semantic Scholar, Dimensions, and BASE (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine) are other sources linking to millions of published papers.

Science.gov searches federally funded science, and ERIC looks for education-related research. eThOS (e-theses online service) is a website provided by The British Library where you can search for UK doctoral theses, giving free full access.

The Zenodo search engine and database let researchers upload papers, software, and data. Papers on any subject are accepted so long as they abide by Open Science requirements.

Citation mapping

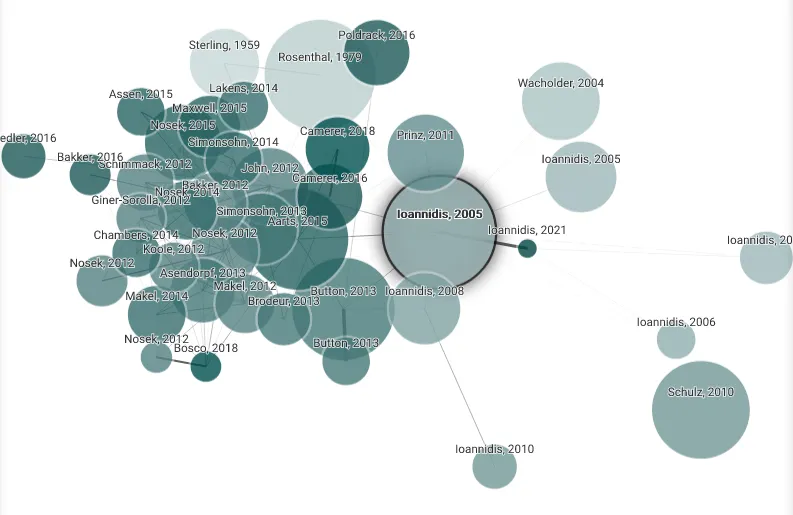

Connected Papers generates a visual representation of papers similar to another article. You can find derivative work, and build a bibliography from the connections.

Connected Papers generates a graphical representation of linked papers.

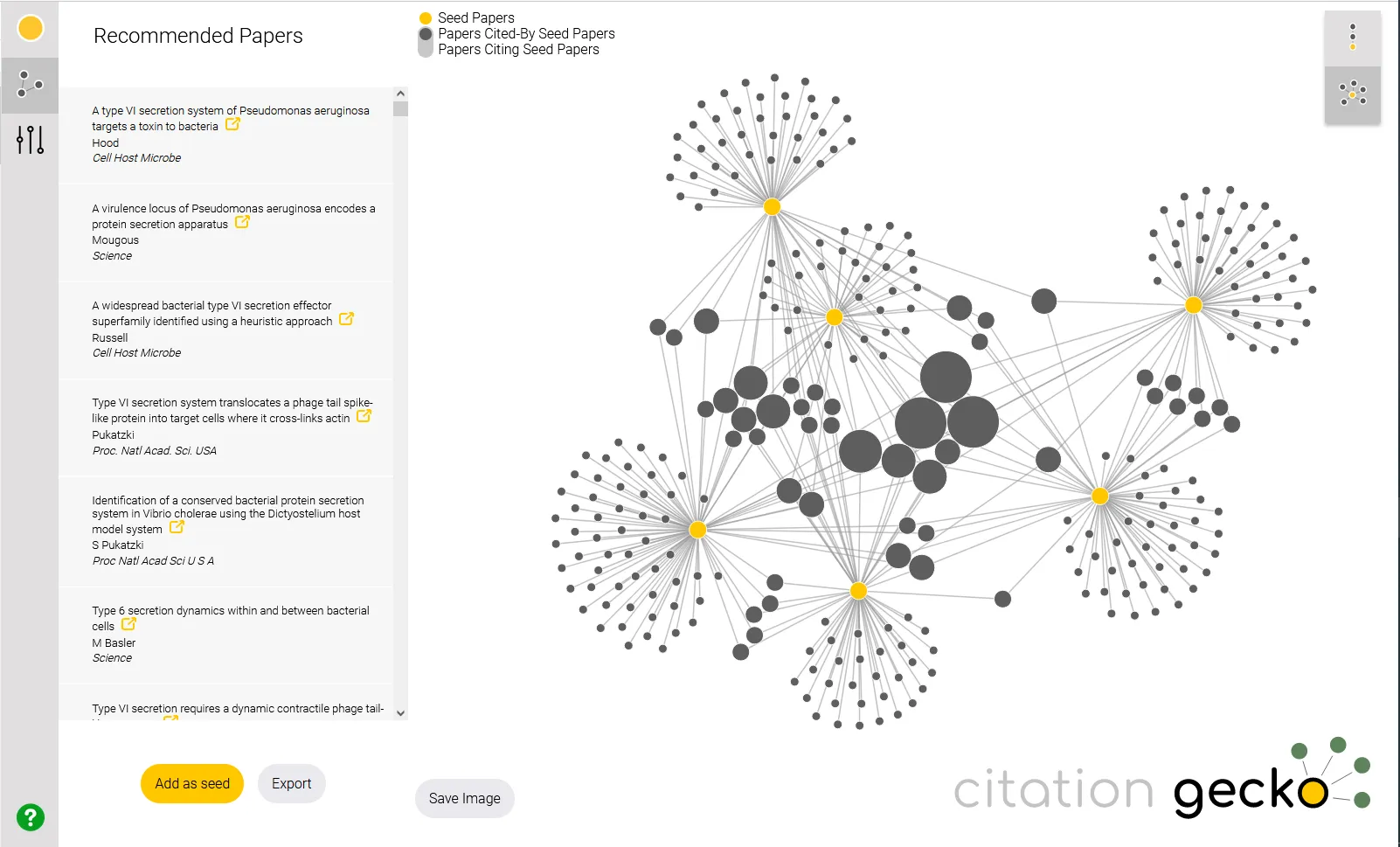

Citation Gecko begins searching from a few relevant papers. It suggests others that might be useful, and with these “seed” papers, Citation Gecko builds a tree of connections.

Citation Gecko uses “seed” papers to begin the search.

VOSviewer constructs bibliometric networks of journals, researchers, institutions, and publications based on Open Alex, Web of Science, Scopus, Dimensions, Lens, and PubMed.

Summarizers

Summarizers aren’t a substitute for reading the paper but can be a starting point for finding important points made in the article. Many require a subscription, but Resoomer, SpinBot, Summarizer, Sassbook AI Text Summarizer, and the Quillbot Paraphrasing Tool are free (sometimes with reduced capability). Scholarcy is a paid service but has a free extension for Chrome and Edge browsers.

The Summarize the Internet and TLDR This - Auto text summary summarizer extensions for Firefox are listed in the Extensions folder.

Download tools

You can often download a paper directly from the search engine found in the Journal articles folder, but if you get stuck, try the Unpaywall, Open Access Button, or CORE Discovery extensions. Library Genesis is a shadow repository for undigitized or paywalled articles but has been accused by Elsevier of internet piracy. Sci-hub is a similar repository where you’re likely to find any article you want.

Note taking

If you want to take notes on the papers you’re reading, Obsidian or Zettlr are excellent alternatives to simple text editors. They allow both internal and external links, use LaTeX in Markdown for writing formulas, and can include images.

Publishing

Depending on your intended audience, you could try Obsidian or Zettlr. LyX is a good editor if your document contains LaTeX, but to get to full control you might need a dedicated LaTeX editor like TeXStudio or TeXnicCenter.

For simple Markdown editing, try ghostwriter or typora. Typora isn’t free but is only $14.99 for installation on three computers.

Sidebars and extensions

Firefox lets you open (or hide) the bookmarks view in a sidebar by typing Ctrl-b. Chrome doesn’t have a sidebar built-in, but you can add the Bookmarks Sidebar extension. Showing bookmarks in the sidebar makes an organized search convenient.

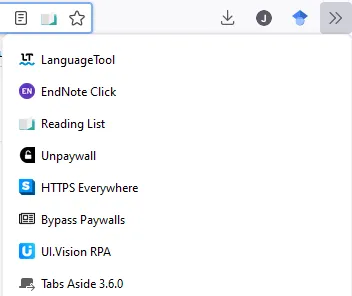

You will probably want several extensions which can clutter the toolbar if you’ve installed a lot of them. In Firefox, there’s an overflow menu where you can drag and drop extension icons if you don’t need to access them routinely. They’re still easily accessible. Just click on the >> at the end of the toolbar to open a drop-down menu of the extensions in the overflow area.

Useful extensions.

Some extensions, like Unpaywall, Open Access, Core Discovery, and Bypass Paywalls could go into the overflow area and be accessed as needed. The Google Scholar button or Zotero connector might be something you want to have more immediately available.

Loading the bookmarks

To get you started, I’ve created a bookmarks HTML file containing the folders shown above, populated with helpful links. You can download the file and import it into your favorite browser.

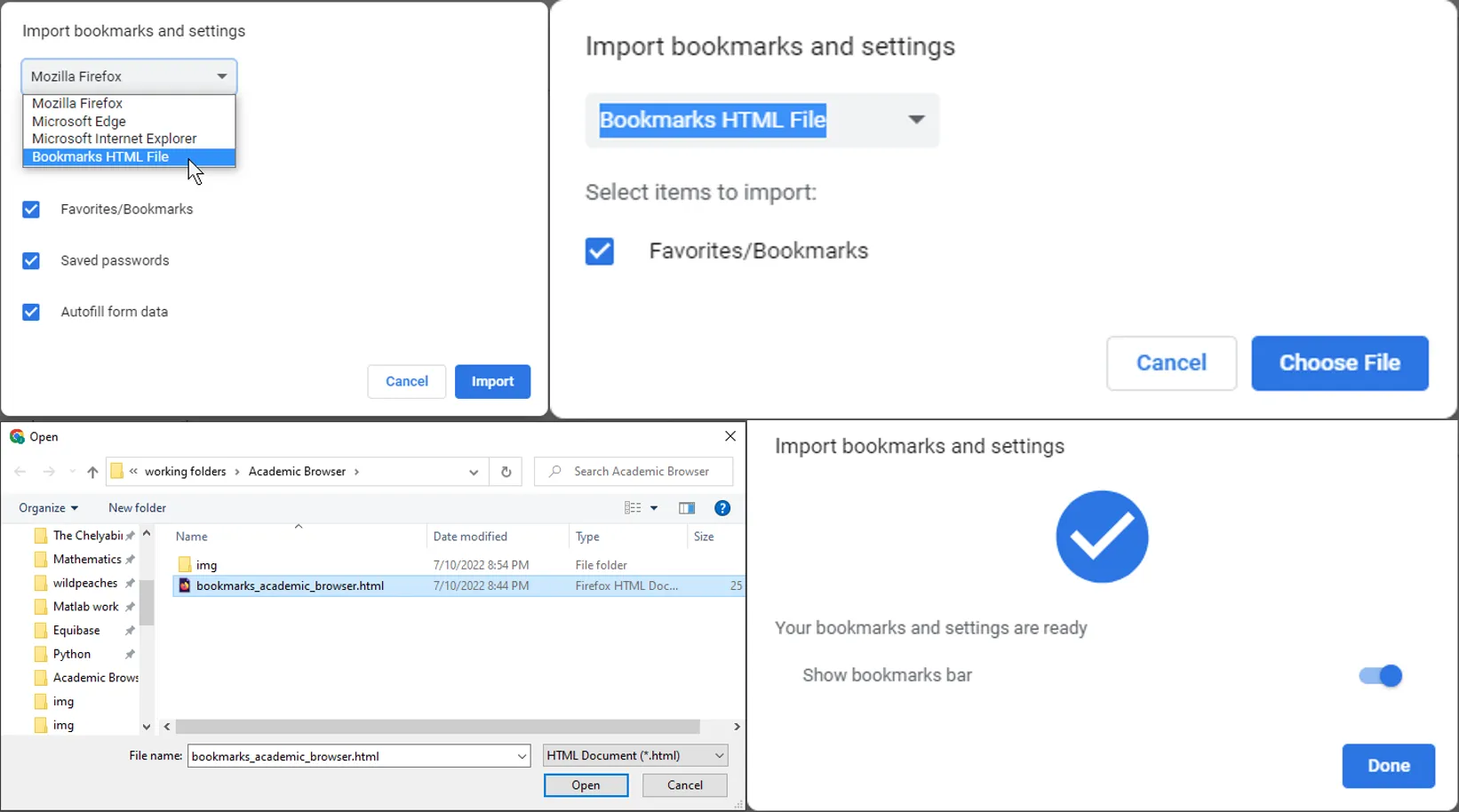

If you use Chrome, click on the three vertical dots in the upper right corner just below the ‘X’ that closes the window. This will open a menu, and you should select “Bookmarks”. Now, select “Import bookmarks and settings …” and in the drop-down box, choose “Bookmarks HTML file”.

Click “Import”, choose the file you downloaded, and open it. After a few seconds, a message box will open showing that you’ve successfully imported the bookmarks.

Importing bookmarks.

Open your bookmark manager and scroll to the bottom to find a folder called “Imported”. Below that, you’ll see the folder “Academic Journal Search”. Drag that folder to a more convenient location, and then delete the “Imported” folder.

You will still need to add any extensions you like from the links in the “Browser extensions” folder.

Your journal search tools should now be ready to help you discover the world of online academic literature.

Limitations of the Bookmark Approach

While browser bookmarks offer a straightforward way to organize research tools, they come with several limitations worth considering:

Sync and Backup Challenges

- Browser sync services may have storage limits for bookmarks

- Sync conflicts can occur when working across multiple devices

- Some institutions block browser sync features for security reasons

- Backup solutions vary by browser and may require manual intervention

Organization Constraints

- Flat folder structure can become unwieldy with many bookmarks

- No tagging system for multiple categorization schemes

- Limited search capabilities within bookmarks

- No built-in annotation or note-taking features

- Cannot easily share selected bookmark collections with collaborators

Version Control Issues

- No tracking of website changes or updates

- Dead links require manual checking and cleanup

- No automatic verification of bookmark validity

- Limited ability to archive webpage content

Alternative Organization Methods

Reference Management Systems

Modern reference managers offer more robust organization features:

-

Zotero Collections

- Browser connector saves full webpage content

- Supports tags, notes, and related files

- Powerful search across saved content

- Built-in collaboration features

- Automatic backup to cloud storage

-

EndNote Online

- Web capture tool for saving resources

- Custom groups and smart groups

- Citation network visualization

- Institutional access management

- Integration with Word processors

Knowledge Management Tools

-

Notion

- Database-style organization of resources

- Multiple views (table, kanban, timeline)

- Rich text notes and embeds

- Collaborative workspaces

- API integration capabilities

-

Obsidian

- Local storage of resources and notes

- Graph view of resource relationships

- Markdown-based note-taking

- Custom tagging system

- Plugin ecosystem for extended functionality

Dedicated Research Tools

-

ResearchRabbit

- Visual organization of academic papers

- Citation network exploration

- Automated paper recommendations

- Collection sharing

- Timeline views of literature

-

Readwise Reader

- Web content capture and organization

- Highlights and annotations

- Spaced repetition for review

- API integrations with other tools

- Mobile-friendly interface

Hybrid Approaches

Many researchers combine multiple tools for optimal workflow:

Example Workflow 1: Bookmark + Reference Manager

- Use bookmarks for frequently accessed search tools

- Save articles and resources to Zotero

- Maintain reading notes in Zotero

- Use browser sync for bookmark backup

Example Workflow 2: Knowledge Management Focus

- Store tools and resources in Notion database

- Use browser bookmarks as quick access points

- Maintain research notes in Obsidian

- Link resources across platforms using URLs

Example Workflow 3: Tool-Specific Approach

- ResearchRabbit for literature discovery

- Zotero for reference management

- Bookmarks for web tools

- Obsidian for personal knowledge base

Choosing Your Approach

Consider these factors when selecting an organization method:

-

Scale of Research

- Small projects might work fine with bookmarks

- Larger projects benefit from dedicated tools

-

Collaboration Needs

- Solo research has fewer sharing requirements

- Team projects need robust sharing features

-

Long-term Storage

- Bookmarks work for temporary organization

- Reference managers better for long-term archiving

-

Technical Requirements

- Institutional security policies

- Available storage space

- Internet connectivity needs

- Cross-platform requirements

-

Learning Curve

- Bookmarks have minimal learning requirement

- Advanced tools need time investment

- Consider available training resources

Each approach has its merits, and the best choice often depends on your specific research context, institutional requirements, and personal workflow preferences. While bookmarks offer a simple starting point, consider graduating to more robust tools as your research needs grow more complex.

Software

- Zotero - a free, easy-to-use tool to help you collect, organize, annotate, cite, and share research.

- Mendeley - Mendeley Reference Manager simplifies your workflow, so you can focus on achieving your goals.

- Qiqqa - The essential free research and reference manager.

- Docear - is a unique solution to academic literature management, i.e. it helps you organizing, creating, and discovering academic literature.

- R - R is a language and environment for statistical computing and graphics.

- RStudio - is an integrated development environment (IDE) for R.

- Obsidian - Obsidian is a personal knowledge base and note-taking software application that operates on Markdown.

- Zettlr - Your One-Stop Publication Workbench. From idea to publication in one app: Zettlr supports your writing process at every stage — from initial notes to journal submission or book manuscript.

- LyX - LyX is a document processor that encourages an approach to writing based on the structure of your documents (WYSIWYM) and not simply their appearance (WYSIWYG).

- Ghostwriter - Enjoy a distraction-free writing experience, including a full screen mode and a clean interface. With Markdown, you can write now, and format later.

- Typora - Simple markdown editor. Used to generate this document.

References and further reading

- Beel, J., & Gipp, B. (2009). Google Scholar’s ranking algorithm: An introductory overview. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics, 1, 230–241.

- Fricke, S. (2018). Semantic Scholar. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106(1), 145–147.

- Hannousse, A. (2021). Searching relevant papers for software engineering secondary studies: Semantic Scholar coverage and identification role. IET Software, 15(4), 215–226.

- Matthews, D. (2021). Drowning in the literature? These smart software tools can help. Nature, 597(7876), 143–144.

- Piwowar, H., & Priem, J. (2022). OpenAlex: A fully-open index of scholarly works, authors, venues, institutions, and concepts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01833.

- Rovira, C., Guerrero-Solé, F., & Codina, L. (2018). Received citations as a main SEO factor of Google Scholar results ranking. El Profesional de la Información, 27(3), 584–592.

- Spinella, M. P. (2003). JSTOR: Past, present, and future. Journal of Library Administration, 39(4), 127–136.

- West, J. D., Jacquet, J., King, M. M., Correll, S. J., & Bergstrom, C. T. (2013). The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLOS ONE, 8(7), e66212.

Image credits

Library image from Francesca Grima, Unsplash Sept. 30, 2019.